Critiquing Palestinian Historiography

or, The Tragedy of Darryl Cooper's Palestinian Wineskins

Introduction: The Vintner of Vignettes

Daryl Cooper of the Martyr Made podcast has a lot going for him in terms of how he communicates historical narratives. He has a deep understanding of World War 1, which makes sense given his obvious interest in how societal dynamics change in response to modernization, and the whole story of that conflict is how empires began dissolving into nation-states. In his series on the origins of the Arab-Israeli conflict, “Fear and Loathing in the New Jerusalem,” Cooper has a shop-talk episode in which he explores how tribal and national societies differ, highlighting how the state apparatus replaces traditional family roles in interfacing with different aspects of life. That episode was a standout for me personally because of its clarity and breadth.

He also has the powerful ability to command pathos with his vignettes of individual actors, such as the legend of Faisal al-Hashemi. Cooper breathlessly tells us about this extraordinary man who strictly abided by traditional Arab hosting customs, honorably protecting the Pasha generals within in his lands despite the tremendous military advantage that would have arisen from slitting their throats as they slept.

His account of what it would have been like to be a Jew in an eastern European pogrom, watching your neighbors suddenly turn on your friends and family—or an Arab during the Kafno famine, going to bed hearing the moans of starving people in the street through the open window—immediately places the listener in a trance-like state. When you listen to Cooper speak, you hover in a space between life and death as you contemplate existence from the point of view of people who had, only moments before he began speaking, been nothing more than distant historical abstractions.

Altogether, then, Darryl Cooper distills this fantastic vintage of historical narrative and deep sociological musing—a new and exciting wine for those of us who are curious about the past—and he proceeds to pour it all into the old wineskin of traditional Palestinian historiography. The result is predictable and tragic: the wineskin splits. And that is the underlying theme of the critique that follows.

The Imitator of Innovation

Let’s begin by considering this word, “historiography.” We all know that history is not a list of events that happened and the order in which they occurred; that’s mere chronology. History is the narrative you create by considering a representative subset of the evidence pertaining to those events, and inferring causal relations to tell a story about what happened.

Because of the politically fraught nature of such an enterprise, it’s possible to tell a multitude of competing stories that each reflect the political agendas of whoever tells the story. To a cynical postmodernist, the story that wins out is a reflection of the agenda of whoever has the power to enforce their story. To an optimistic empiricist, there exist objective standards that all parties can agree to in the course of adjudicating competing narratives. To some degree, both perspectives have their strengths.

For now, what’s important to consider is the historiographic landscape of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The historiography presented by Cooper reflects the Palestinian point-of-view; not a Palestinian point of view, but the Palestinian point of view.

In contrast to Western (including Israeli) historiographies, which are distinguished by their pluralism, the Palestinian historiography is characterized by its rigidity and stagnancy. This is as true for historians living in Palestine as it is for those living in its diaspora, like Rashid Khalidi or Nur Masalha. Insular, totalitarian societies like Palestine have an unfortunate tendency to violently penalize deviation from orthodoxy. If you’re a Palestinian, and you publicly question the basic assumptions of your society’s historiography—like the idea that Zionism was a colonial enterprise, or that the conflict originated with the Balfour declaration and that previously, Jews and Arabs lived together in peace—you run the risk of contracting an acute case of lead poisoning. If you’re living in New York City, and you’ve got people in Nablus or East Jerusalem, you need to be equally careful about what you write down in your books, lest you receive a phone call informing you about some very regrettable developments concerning your “Zionist collaborator” family.

In contrast, Western historiographies are dynamic and varied. Israeli scholarship encompasses views ranging from pro-Palestinian, settler-colonial narratives offered by the likes of Ilan Pappe, to pro-Zionist tales of treacle heroism championed by Netanel Lorch, to everything in between—be it Benny Morris’ unflinching New Historiographic examinations of archival documents showcasing Israeli war crimes, Efraim Karsh’s impassioned defenses of the “Old Historiographic Guard,” or Anita Shapira’s thirty-thousand foot narrative.

Regardless of whose historiography you like best, you run the risk of being called a racist apologist for violence of some stripe or other. That’s pretty much inevitable when discussing this conflict. But when browsing Western historiography, you can at least enjoy the benefits of cognitive flexibility and creative energy of the sort in which Palestinian historiography, with its stifled and static intellectual environment, is found lacking.

The upshot is that when Western narratives are challenged by new information, they can adapt and revise, growing stronger than before. For example, there is little doubt that by incorporating the harsh realities of Israel’s past, which Old Historians like Lorch have traditionally omitted, New Historians like Benny Morris and revisionary traditionalists like Anita Shapira have strengthened the Zionist side of the argument.

This stands in contrast to the Palestinian narrative, which remains mired, decade after decade, in harshly enforced orthodoxy. Consequently, it suffers from the limitations of all stagnant narratives: it cannot adapt, cannot respond effectively to facts that challenge its basic assumptions.

And this is the trap that Cooper falls into. By adopting the standard Palestinian assumptions and narrative, he unwittingly inherits all of its defects, which even his immersive style and sociological depth cannot fix. Ironically, despite enjoying the reputation of a history enthusiast who challenges established narratives (at least, in other contexts), Cooper here becomes yet another reciter of an orthodoxy whose contradiction will get you in trouble in certain parts of the world. Those who have only ever heard Western historiographies to the exclusion of the Palestinian one might therefore mistake him for a maverick (at least on this topic), oblivious to the fact that Cooper is recycling a story as old as it is flawed—albeit in his own unique style.

The Wears in the Wineskin

The key assumptions behind Palestinian historiography are as follows:

Jews and Muslims lived together in peace before Zionists migrated to Palestine.

The incoming Zionists were colonial invaders with no connection to their presumed homeland.

Palestinian Arabs were nationally differentiated from the Arabs of the surrounding region; the Arabs of Palestine were in some fundamental sense distinct, as a political unit, from the Arabs of Syria-Lebanon, the Arabs of Transjordan, and the Arabs of Egypt.

The Palestinians were the unwitting victims of British and Zionist machinations, understandably defending themselves from colonial imposition by alien forces. Their actions and shortcomings fundamentally came down to the fact that they were honest to a fault, the victims of both tragic circumstances and colonial scheming. Had they only been more shrewd, had they only possessed the worldly resources necessary to direct their confusion and pain towards more productive means of resistance, they would not have ended up in their deplorable position today.

This last one is for an English-speaking audience only. For an Arab-speaking audience, the Jews are evil and everything written about them in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion is true. But when addressing an English-speaking audience, like Daryl Cooper—and through him, the audience of his podcast—the Jews are painted in a more humane light. This serves the function of not immediately disqualifying the Palestinian narrative in the eyes of the Western world. However, it carries over that most essential feature of the Palestinian version of events: it ultimately regards Jews as bearing the brunt of responsibility for Palestinian suffering. The summary of this final assumption that they generally opt for is that “the Zionists punished Palestinians for the crimes of Europe.” In this formulation (at least, for English-speaking audiences), the Holocaust did happen, it was bad, and the pogroms and mass killings endured by the Jews were undeserved. But it also didn’t justify the colonization of Palestine.

Taken together, these are the fundamental assumptions of all Palestinian historiography. They form the stagnant wineskin of the story that Daryl Cooper goes on to fill with a delightful new vintage that incorporates his particular strengths as storyteller and amateur sociologist. Let’s tackle each of these assumptions to get a sense of where exactly Palestinian historiography goes wrong, and how Cooper’s presentation of that narrative exacerbates its weaknesses.

Assumption #1: The Peaceful Muslim Locals

Perhaps the most foundational myth of Palestinian historiography is the notion that prior to the arrival of the Zionists, Jews and Muslims lived together in peace. This myth is essential to their version of the story because it establishes the innocence of the Arab Muslim population from the outset, putting to rest any foolish and naive notion that religiously motivated hatred might be implicated in the violence of the Arabs of Palestine.

Indeed, Cooper himself castigates anyone who might suspect that Islamically motivated bigotry might have had anything at all to do with motivating the conflict in the early days of Zionism. He assures us that such views are naive and misinformed. By his account, the nature of Palestinian Arab resistance was fundamentally of an anti-colonial character, and religion served only to bolster and unify the disparate tribes of the region (at least, to some extent.) Islamic religion, in his view, played only an incidental role in the conflict rather than a fundamental one.

But that doesn’t stop Cooper from talking about religious extremism and its role in igniting the conflict; it only stops him from talking about Islamic religious extremism specifically. He refers to the ominous Old Testament texts alluded to by certain Zionist actors during times of heated conflict with the Arabs, which recalled genocides of Canaanite groups like the Amalekites in the same land that the Jews were once again trying to win.

Cooper also belabors the apocalyptic theology of at least two different Christian Zionists: one who served in an administrative capacity, and another who assisted the British in brutally suppressing the Arab Revolts of the 30s. He emphasizes at length that people like this have no moral compunctions about inflicting atrocities against the local Arabs in the name of the Zionist cause, owing to their conviction that by fulfilling the prophecies of the New Testament, they were inaugurating the end of the world.

And yet, in this land which is so holy to the three great world religions, Cooper sees fit not only to uniquely neglect any causal role played by the one representing the side whose historiography he’s repeating, but outright dismisses any such suggestion as baseless. He has time to tell us about religious extremism with scriptural basis in Jewish and Christian theology, but has no time whatsoever to talk about their Islamic counterpart.

This omission is not unique to Cooper—he’s just doing what Palestinian historiography has always done—but the absence of any mention of Islamic fundamentalism is felt even more acutely by his choice to describe, at length, the role of Jewish and (especially) Christian religious fundamentalism. This feature of his unique historical vintage thus reacts violently to the tattered old historiographic wineskin meant to contain it.

Not once do the words “dhimmi” or “jizya” appear in the entirety of his series, and that silence is deafening. It continues the time-honored Palestinian tradition of negating, denying, and erasing the long and painful history of institutionalized Muslim violence against the Jews over the course of 1400 years. So let’s take a moment to rectify that.

The Origins of Dhimmitude

In Islamic societies, Christian and Jewish “People of the Book” are permitted to remain in the territories conquered by the armies of the Prophet Muhammed and his followers under certain theologically motivated conditions. It pays to momentarily elucidate what exactly those motivations were.

The foundational texts of Islam clearly state that the Jews are a cursed people. When the Prophet first encountered them in the 7th century CE, they had already been exiled from the Land of Israel for hundreds of years. By Muhammad’s reckoning, this was proof that they were being punished for something. And that “something” turned out to be the central thesis of the religion he developed: the Jews had corrupted monotheism. Their false theology had led them into disaster, and it was now up to Muhammad to correct the record with Islam—that version of monotheism which, according to him, was the original version of Judaism before the Jews corrupted it.

Early on in his career, the Prophet Muhammad apparently felt spurned by the Jewish theologians who’d dismissed him as yet another illiterate know-nothing when he showed up to enthusiastically discuss his theological musings with them. One suspects that his feelings of anger and rejection might have played some role in his decision to compare Jews to dirty animals in the new religion that he went on to found and spread by word and sword; it comes out in prophecies like the one assuring Muslims that on the day that they’ll defeat the Jews, every stone will cry out, “there is a Jew hiding behind me, so kill him!”

It is open to speculation whether those feelings had any purchase in his decision to lead his armies in a raid of the Jewish settlement of Khaybar, whose inhabitants went on to be raped, murdered, and enslaved. It is likely that their violation of treaties, among other political considerations, accounted for the lion’s share of what influenced this (and many other) acts of wanton violence against the Jews. Among his many victims was a Jewish woman named Safiyya bint Huyayy, who was forced to watch Muhammed’s men destroy her home and behead her husband. She was abducted as a sex slave and made to convert to Islam in exchange for the privilege of becoming the Prophet’s tenth wife (Islamic tradition assures us that she fell in love with him on the horse ride away from the community he’d just finished slaughtering).

Regardless of his intentions, his words and actions are a matter of historical record, and they would set the tone for how Jews were to be regarded in the societies inspired by his revelations. In clarifying Muhammad’s attitudes towards Jews, which seem to reflect a character torn between longing for Jewish approval and raging at Jewish rejection, these details help us contextualize the reason for the not-so-peaceful treatment of Jews at the hands of Muslims, who throughout history revered the Prophet as the highest exemplar of virtuous behavior. They help us understand how the Islamic attitude towards Jews has been shaped by theological and sociological considerations.

The Jews were (are) an ancient people with over 1000 years of history preceding the creation of Islam. From a theological point of view, this fact alone makes Judaism an inherent threat to the legitimacy of Islam. And Jews are still around, even after the Prophet Muhammed shared his revelations with the world, then it can only mean one of two things: either the Jews are every bit as wicked as Muhammad claimed, or the Prophet was a hateful, raving, murderous lunatic.

And in a society where the behavior of a hateful, raving, murderous lunatic is sanctified as the highest standard of morality, second-class citizenship functions as a mechanism of legitimation. If the Jews (and Christians) are kept in a subordinated and humiliating role by their Muslim overlords, then this must surely weigh in favor of the claim that Muhammad was right all along; the wicked unbelievers are receiving their just fruits. And those who cave under the pressure to assimilate and convert, thereby earning first-class citizenship among the sons of Ishmael, must surely have been swayed by the obvious truth and morality of Islam.

The status of “People of the Book” as second-class citizens, to be abused, extorted, and—whenever they forget their proper place beneath the heels of Muslims—pogromed, serves a societal function. The wretched condition of the Jews assures the Muslim polity of the truth of their own doctrine. It assures them that the scales of cosmic justice are balanced by the divinely inspired words of the Quran.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the treatment of Jews under the various Islamic Empires is only ever referenced in a positive fashion when contrasted with European Christians, who until modern times had mistreated their Jews for parallel reasons (albeit to a harsher degree.) Whenever I hear someone claim that the Jews had it better under Islam than Christianity, I cannot help but be reminded of the old American slavers’ insistence that their treatment of blacks was less severe than that of Arabs, who had been known to castrate and murder their slaves en masse. The purpose of such whataboutism is never to insist upon historical accuracy, but rather to abrogate responsibility. And in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, this remark—“Muslims treated Jews better than Christians did”—is little more than a cynical attempt at an alibi.

We can dismiss it by considering some features of the second-class citizenship that Muslim societies inflicted upon their Jews. I have already mentioned the two terms of central importance: dhimmi and jizya. Let’s take a moment to examine what these things are and how they shaped the cultural landscape of the pre-1948 conflict in Palestine.

The Wages of Dhimmitude

Dhimmi is the name given to the “People of the Book,” whose status as second-class members of Islamic empires was enshrined in law. The degree of humiliation varied across time and place. It was better, by and large, to be a Jew in the Abbasid Empire than the Mamluk Empire, or a Jew in the final years of Ottoman Jerusalem than in the first years of Ottoman Jerusalem. Regardless, the message sent to the Jews was always clear: you are an inferior people and you need to know your place.

Whether by limiting access to institutions, mandating deference to Muslims, suppressing expressions of non-Islamic religious practice, forbidding residence in houses higher than those of Muslims, or making it illegal to ride a horse, societies that institutionalized the practice of distinguishing dhimmi from Muslims ensured the perpetual humiliation of the Jews. They made Jews identify themselves by wearing yellow badges on their clothes centuries before Hitler got the idea.

Signor Pananti, a 19th century traveler across the Ottoman Empire, aptly summarized the condition of dhimmitude:

There is no species of outrage or vexation to which the Jews are not exposed. The indolent moor with a pipe in his mouth and his legs crossed, calls any Jew who is passing and makes him perform the offices of a servant. Even fountains were happier, at least they were allowed to murmur.

Of the many symbols of submission that were inflicted upon dhimmis, the one which stands out most is the jizya. As with the word “dhimmi,” which euphemistically translates to “protected person,” jizya translates to “poll tax.” This tax was not issued in exchange for any kind of political representation; dhimmitude precluded any such possibility. The “poll tax” was issued in exchange for the “protection” of “protected people,” in more or less the same way a “fee” is paid out by a business owner in exchange for a mob boss’ “protection.” And in the subsistence-level living conditions that characterized Jewish life under Islamic rule, the extortionate jizya could mean the difference between eating and starving. Perhaps no other instrument–not even the slings and arrows of Islamic conquest–proved so effective at persuading Jews to convert to the faith that preaches “no compulsion in religion” than the jizya.

Even the famed theologian and physician, Maimonides—often touted as a shining example of a Jew who had thrived under “tolerant” Islamic rule—had some choice words for those who had imposed dhimmitude and the jizya upon him. Writing in The Epistle to Yemen in 1172, Maimonides remarks:

God has entangled us with this people, the nation of Ishmael, who treat us so prejudicially and who legislate our harm and hatred…. No nation has ever arisen more harmful than they, nor has anyone done more to humiliate us, degrade us, and consolidate hatred against us.

He continues:

We bear the inhumane burden of their humiliation, lies and absurdities, being as the prophet said, ‘like a deaf man who does not hear or a dumb man who does not open his mouth’.... Our sages disciplined us to bear Ishmael’s lies and absurdities, listening in silence, and we have trained ourselves, old and young, to endure their humiliation, as Isaiah said, ‘I have given my back to the smiters, and my cheek to the beard pullers.’

Four centuries later, another Jewish scholar and physician, Solomon ibn Verga, authored the Shevet Yehudah, in which he recounted an incident where the Jews had foolishly forgotten that their proper place was beneath the boot heel of the Prophet’s loyal followers. According to him, a sultan had been blessed with a highly trusted and influential Jewish advisor, and the regional Muslim population held him in high esteem. But when he died, instead of appointing a Muslim to the role, the sultan appointed the Jew’s son. This led to widespread anger and, ultimately, a pogrom against the local Jewish population. Such stories were by no means uncommon in the Arab Muslim world. Whenever the Jews had the temerity to forget their proper place, the local Muslim population was reliably on hand to remind them.

Jews were not the only dhimmi to be issued periodic reminders of this sort. Beginning in 1839, the Ottoman Empire attempted to modernize with a series of reforms called the Tanzimat, which aimed at granting more rights to dhimmi. By 1850, these reforms had noticeably eased commercial restrictions upon Christian merchants in Aleppo. This sparked discontent among the local Muslims, who perceived their neighbors’ burgeoning equality under the law as a threat to the divinely sanctioned economic advantages conferred to them by the Quran’s policy of extorting non-Muslims. The resulting riots left dozens of Christians dead in their homes and churches.

Thirteen years later, in a non-Muslim society on the opposite side of the Atlantic, another reform would be issued. That Proclamation similarly elevated the legal status of a different subjugated minority.

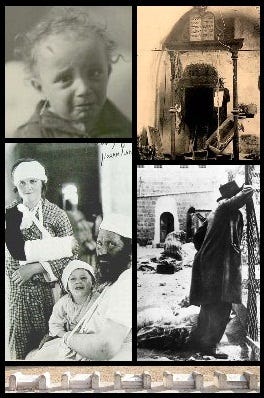

And as it was in the Levant, so it was in Dixie; even relatively modest attempts at legislating equality under the law soon yielded bounties of strange fruit, with blood on the leaves and blood on the root. There seems to be something cross-cultural about the phenomenon where the political elevation of a formerly abused and humiliated people towards a state of political equality is soon followed by the frenzied bloodlust of their former tormentors. Whether that murderous rage is found among the broken stainglass in Aleppo, the burning crosses in Dixie, or the raped and murdered throngs of Jews in 1920 Nebi Musa, 1921 Jaffa, and 1929 Hebron, it seems to materialize wherever and whenever a formerly subjugated people refuses to accept their proper place.

In the case of the American South, the peculiar institution that was overthrown had principally rested upon a couple centuries of tradition. But in the case of 20th century Palestine, the institution in question had persisted for 1300 years, its authority divinely ordained. As the Arabs of Palestine enthusiastically chanted during protests in 1920, “This is our land! The Jews are our dogs!” Take note of the phrasing. They did not say, “The Jews are dogs!” They said, “The Jews are our dogs!”

There is much more to say about the role Islam played in fostering the virulent hatred that Palestinian Muslims held for the Jews who refused to accept their proper place, but the fact that Palestinian historiography refuses to acknowledge the matter—much less honestly engage with it—is damning. In choosing to adopt that historiography, Cooper has not only inherited this crippling defect of the Palestinian wineskin, but has amplified its weakness by imbuing his narrative vintage with outsized attention to the worst elements of Jewish and Christian theology whilst remaining silent about Islam. These selective omissions and distortions, which Cooper has inherited from the historiography he recites, are consistent with the ongoing campaign of denial, erasure, and historical negation that characterizes the Palestinian side’s plea of innocence.

The myth of peaceful coexistence between Muslims and Jews prior to the commencement of the Zionist enterprise plays a central role in Palestinian historiography, and will be revisited repeatedly as we make our way through the other assumptions. For now, let’s proceed to the second foundational assumption of that historiography.

Assumption #2: The Rootless Cosmopolitan Invaders

Palestinian historiography has always been burdened by bitter and perverse ironies, and few things make this more clear than its characterization of Zionist migrants to the land. Perhaps the chief irony of the Palestinian denial of continuous Jewish connection to the land throughout history, both in spiritual and material terms, is that the Jewish claim to the land would have been weaker if not for the existence of the aforementioned jizya. Had the Arabs of Palestine not enacted extortionate taxes upon the Jews following their conquest over Jerusalem in 638 C.E., thereby forcing native Jews to either convert or flee to another territory to avoid the jizya, the diasporic Jews scattered throughout the world would not have been as incented to send money to support their dhimmified brethren, thereby maintaining both an ongoing political and economic connection to the land over the course of 1300 years.

If not for the dhimmitude forced upon the Jews of Palestine, this ongoing material connection to the land by Jews in the European, Arabic, and African diasporas might never have been needed to help sustain a continuous Jewish presence in the region. In this counterfactual, Zionists would only have been able to point to the ideological component of Jewish connection to the land, which is characterized by the national character of the Jewish identity. Let’s take a moment to examine that character.

The Story of the Jews (Abridged)

The word “Islam” is Arabic for “submission,” referring to the defining spiritual ethos of that faith: submission to the will of God. The word “Christianity” is derived from the Greek “Christos,” the literal meaning of which—“anointed one”—refers to the central subject of worship within that faith.

In contrast, the word “Judaism” is not derived from abstract spiritual concepts, but from the Kingdom of Judah, which has a particular place and time in history. To be a Jew is to be “of Judah.” True enough, that kingdom was named after one of the twelve original tribes of Israel, whose name could in turn be interpreted as something spiritual like “Thank God,” but this was just a matter of historical happenstance. Had one of the other tribes—say, Naphalti, whose name means “twisting”—been the one to develop a Kingdom at that time, then the Jews would instead have been called “Naphaltists.” (In retrospect, it is fortunate that this did not happen. The name “twisted people” would have given antisemites throughout history that much more material to rationalize their hate, but I digress.)

The point is, Jewish national identity traces its origins to a specific place and time in history, beginning approximately 930 B.C.E in the Judean Mountains of the Southern Levant. The naming convention of Judaism alone—the fact that it has a territorial rather than spiritual basis—should give pause to those who deny the authenticity of Jewish national identity. To Cooper’s credit, he doesn’t explicitly support the common Palestinian talking point that “Jews are a religion and not an ethnicity,” but the point is still worth making because it helps to develop context that undercuts much of the historiography that he repeats.

By his account, the Jews of Europe had no connection to their ancient homeland. The metaphor he uses in the podcast series invites you to imagine that you’re living in a house, only to find an intruder barge in. The intruder claims a portion of the house for himself on the grounds he used to own it and that he really needs a place to stay right now. Even if you initially consent, he proceeds to invite all his new friends, who then proceed to antagonize and provoke you. After being a bad and invasive new tenant, he ultimately throws you out and claims the whole property for himself, leaving you homeless.

Let’s modify this metaphor to make it more closely resemble reality. The “intruder” in question has, over the course of his entire absence, contributed to the mortgage; the Jews living in diaspora economically supported the Jews living in the Land of Israel by sending money to their subjugated brethren for the purpose of maintaining a continuous Jewish presence in the homeland. Why? Because the “intruder” never lost his sentimental connection to that property after being thrown out.

Every day, three times a day, diasporic Jews around the world would turn in the direction of Jerusalem and recite a series of prayers called the Amidah, one of which begged God to let them someday return to their homeland. This activity occurred continuously over the course of two millennia in exile, alongside pilgrimages to the Holy Land and diasporic charities in the form of halukka, which contributed to the region’s economy.

The Jewish holidays all make reference to events that have happened to the Jewish nation, from mythologized accounts of how the national identity formed through the Exodus (Passover), to the event symbolizing the successful revolt of the Maccabees–the original Zionists–against the occupying Seleucid Empire, thereby restoring national independence (Hanukkah). They encompass both apocryphal stories, like the time a sexy Jewish lady saved the entire nation by winning the heart of a Persian king (Purim), to historically verifiable events, like the assassination of the last governor of Judah (commemorated as a national day of mourning with the Fast of Gedaliah). The Passover Seder concludes with the phrase “Next year in Jerusalem,” symbolizing both the historical connection to the land and the enduring hope of return.

Even Rosh Hashanah, the new year of the Jewish lunar calendar, was initially calibrated with respect to Jerusalem. Prior to the adoption of a mathematical convention, time was marked by the appearance of the new moon. Since this can vary from location to location (a new moon seen in Beijing might not be visible over Jerusalem), even time is kept by the Jews with reference to the harvest cycle of their homeland.

Given that the Jewish national identity formed in premodern times, a mystical and religious superstructure was overlaid atop its secular basis. And though these spiritual elements persisted over the millenia spent in exile, they effectively functioned to maintain the Jewish national identity over the generations by theologizing its national characteristics. Cooper himself discusses, at some length, how rituals like circumcision functioned to differentiate the group from the nations it found itself dispersed among, and correctly characterizes much of the Old Testament as an instruction manual for the preservation of identity while in exile.

And that preservation of Jewish identity was maintained even in the face of immense pressure to assimilate. The burnings, Inquisitions, pogroms, and second-class citizenship that have characterized Jewish life in exile could all have been avoided, had the Jews only abandoned their national identity through conversion to the dominant faiths, which unlike Judaism are international in character. Unlike Christianity or Islam, which spread across many nations, Judaism’s identity has always been tied to the land of Israel, even while in exile.

And during that time, the Jews held on to who they were. Subordinated as they were, they still retained their material connection to the Land of Israel by sending money to the Jews still living in the conquered homeland. This connection was maintained throughout the ages; the diasporic Jews continued clinging to their identity. They endured humiliation and mass slaughter for countless generations, holding on to the hope that someday, somehow, God would deliver them to the promised land once more.

But as the centuries stretched onwards into millennia, and the diaspora grew ever more scattered to the corners of the earth, that day never came. God remained silent.

The Jewish National Identity Modernizes

Enter the Enlightenment, which took Europe by storm. The Jews living in exile had, by and large, split into the religious and the atheistic; those who had abandoned their national identity through conversion were no longer Jews. (An argument can be made—though I won’t press it here—that those who’d abandoned their national identity through the adoption of anti-nationalist ideologies like communism also ceased to be Jews.)

In the Age of Enlightenment, the separability of church and state became an essential feature of modern national identities. This has remained a fixture of the (then-new) ideology of nationalism, as well as its associated concept of the nation-state. Many former monarchies and theocracies witnessed their transformation into modern, secular nation-states, reflecting the ongoing evolution of national identity through the ages.

The Jewish national identity had already undergone a number of changes in its own history, from its monolatric origins in Canaanite religion to its monotheistic innovation under King Josiah during the 7th century C.E.; from its Hellenization circa 400 B.C.E, to its rabbinization circa 200 C.E. As with other nations of the 18th and 19th centuries, the Jewish national identity would ultimately undergo a parallel form of modernization, aligning it with the conceptions put forth by nationalist ideology. The name of the movement that was ultimately responsible for modernizing the Jewish national identity is Zionism.

It should come as no surprise that the initial Zionists were atheists. Many supported socialism, and nearly all were romantic idealists. Unlike their religious counterparts, who took seriously the rabbinic injunction not to reestablish a Jewish nation in the Holy Land until the arrival of the messiah, the Zionists grew tired of the silence of God and decided to take matters into their own hands. Their arguments for the establishment of a modern nation-state rested not on theological reference to “the Chosen People” trope—an innuendo that Cooper bizarrely slips into his series early on—but rather upon secular, Enlightenment notions of national revival.

The material and ideological connection to the historic homeland, maintained over two millennia, was the justification for the Zionist enterprise. And thus the program proceeded in earnest; Jews from around the world, from Yemen to Europe, mass migrated from 1882 to 1948.

They departed for the territory that their ancestors had prayed for a return to, and whose holidays and traditions they had maintained across countless generations. They ascended to that place which their families had, even in the destitute and miserable conditions inflicted upon them in foreign lands that distrusted and despised them, materially contributed to via what meager charity their ghettoed communities could scrounge. They returned to that home which their national identity was tied to, and which their ancestors never gave up, even though doing so would have spared them and their descendants from bottomless depths of humiliation and torment, from pogroms and genocide.

And upon arriving at the promised house, these “intruders,” who had never lost their spiritual or material connection to it, got to work rebuilding it. But even if this part of Cooper’s analogy was wrong, what about the rest? Should we just ignore the fact that the house was already occupied? How could the original inhabitants—who we will no longer call “intruders”—justify their seizure of a property that now belonged to somebody else? Well, that’s the third assumption of Palestinian Historiography. Let’s proceed to address it.

Assumption #3: “The Palestinian People” were Already Here

One of the more jarring junctures where the wineskin splits is at the subject of Palestinian national identity. Cooper assures us in the first episode that Zionists came in with the presumptuous colonial assumption that the Palestinian Arabs were ethnically undifferentiated from the other Arabs, and he suggests that this assumption was wrong. But strangely, when he later delves into the differences between the social dynamics of tribal societies and societies with strong state institutions, he lends support to the claim that the Palestinian national identity did not exist until after the Zionists arrived.

Indeed, he talks at length about their national aspirations to join Greater Syria, as well as the notable Nashashibi clan’s attempts to absorb the region into Jordanian territory. Other Arabs held a vote in 1920, the outcome of which reflected the widely held view that Palestinian Arabs should be absorbed into Syria. You don’t have a Palestinian national identity if you’re trying to get absorbed into Jordan. You don’t have a Palestinian national identity if you’re trying to get absorbed into Syria. Something about this story isn’t adding up. And even though some people, particularly those engaged in organized insurgencies against both Jews and Brits, may have been thinking along the lines of Palestinian national identity, there’s no good reason to believe that such views were widespread among the Arabs.

Cooper seems to oscillate between critiquing Zionist assumptions and agreeing with them. He wants to condemn them for failing to acknowledge the national characteristics of the people they’re ostensibly colonizing, yet also wants to explore the sociological dynamics of the pre-national identity of these people when explaining their failure to develop state institutions during the Mandate period–one essential area where the Jews were successful.

Cooper's storytelling, vivid and immersive, bursts open when confronted with the contradictory realities of Palestinian national identity. By trying to contain this complex, evolving identity within the rigid framework of Palestinian historiography, which insists upon a colonial relation between Zionists and Arabs, the narrative structure collapses under the pressure of its own contradictions.

Palestine: 2000 Years of Imperialism and Colonialism

As I’ve mentioned earlier, Palestinian historiography is burdened with bottomless ironies. But this is perhaps nowhere more evident than in the name they chose for themselves: “Palestinians.”

The name “Palestine” first appears in the historical record in the 5th century BCE when Herodotus wrote of it as “a district of Syria” in The Histories. He was apparently under the impression that the Philistines, who we now know to have emigrated from Crete circa 1175 BCE, was the dominant political unit conquered by the Assyrians when they captured the southern Levant.

In reality, the region was populated by all manner of peoples, including the Israelites. Of these, the most enduring were the ancient kingdoms of Israel and Judah. Sometimes these kingdoms were independent and free. Other times, they were a district within a greater imperial power.

Ancient religious tradition characterizes the Philistines as the enemies of the Jews, and their numbers dwindled as the region changed hands from empire to empire. By the time the Romans conquered the region and renamed it Judaea (a derivative of “Judah”), the Philistines had long since ceased to exist as any kind of political unit.

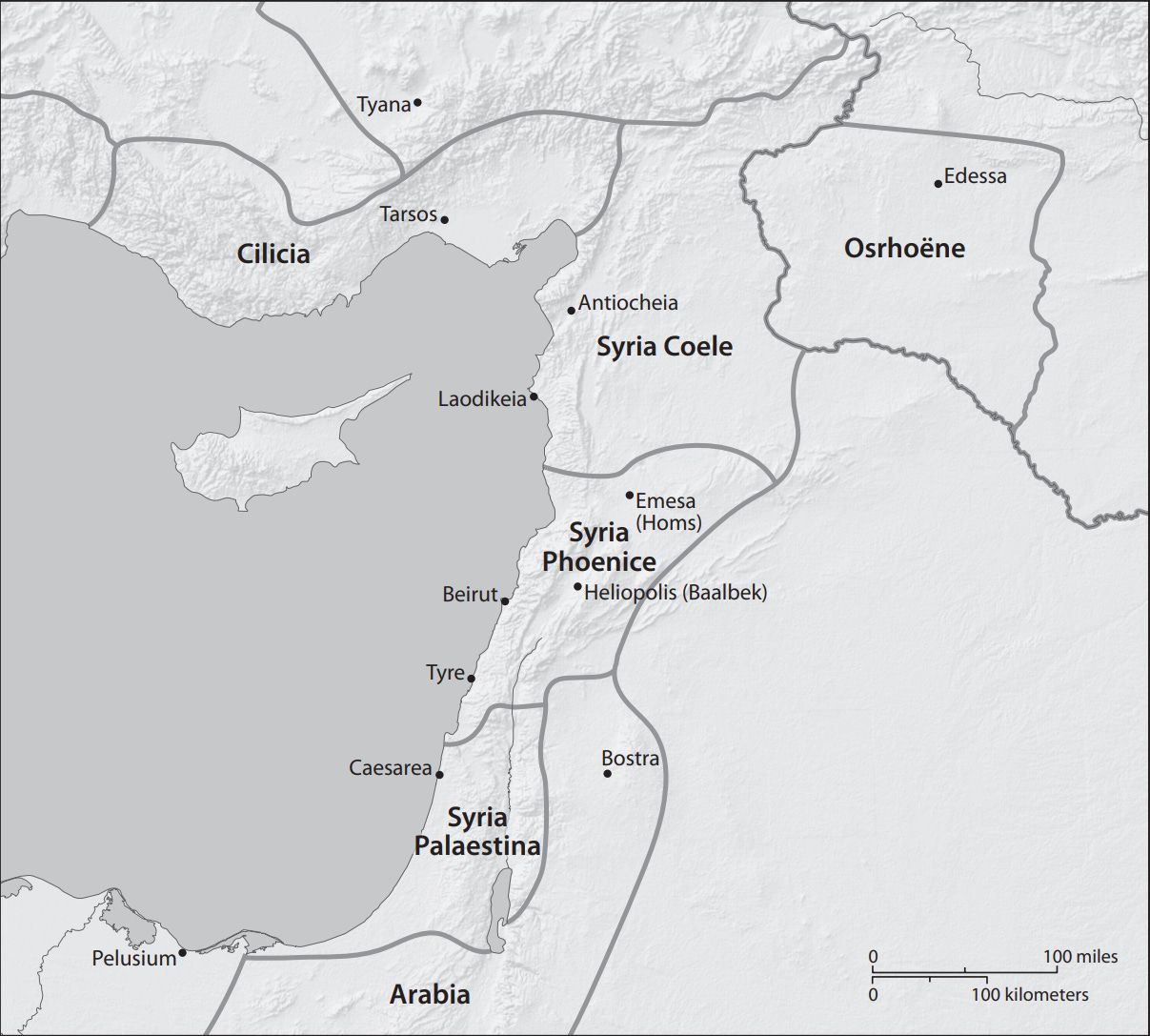

But the memory of their role as the nemeses of the Jews lived on, and in an act of imperialistic cruelty, Rome renamed the province “Syria Palaestina” upon suppressing the Bar Kokhba revolt in 136 CE. The spirit in which they chose this name is akin to that which might motivate modern-day Israel’s enemies to call the region “Hitlerland;” The purpose of this name was to humiliate the Jews and crush their national spirit.

That cruelty was promptly compounded by the expulsion of the majority of Jews from their homeland, kicking off the 2,000 year ordeal that would come to define most of Jewish history. Thus did the Roman Empire, seeking to destroy the Jews as a political unit, inflict the second exile in an attempt to erase all memory of Jewish connection to the homeland.

But the Jews did not forget. After two thousand years in exile, the Jews retained their national identity–updated it, even, along with all the other nations that had been touched by the Enlightenment.

Meanwhile, the region changed hands many more times. The Byzantines, Egyptians, and Turks were only some of the many foreign powers that would come to occupy the land. Consequently, its name and borders constantly changed.

The name “Palestine” remained in use along the same lines as the names “Dixie” and “Scandinavia.” Dixie and Scandinavia are not, and never have been, the names of sovereign political entities; these have only ever been the names for certain regions. Similarly, Palestine, also known as “The Holy Land” and other such names, was never sovereign; it was only ever a region under the jurisdiction of foreign powers.

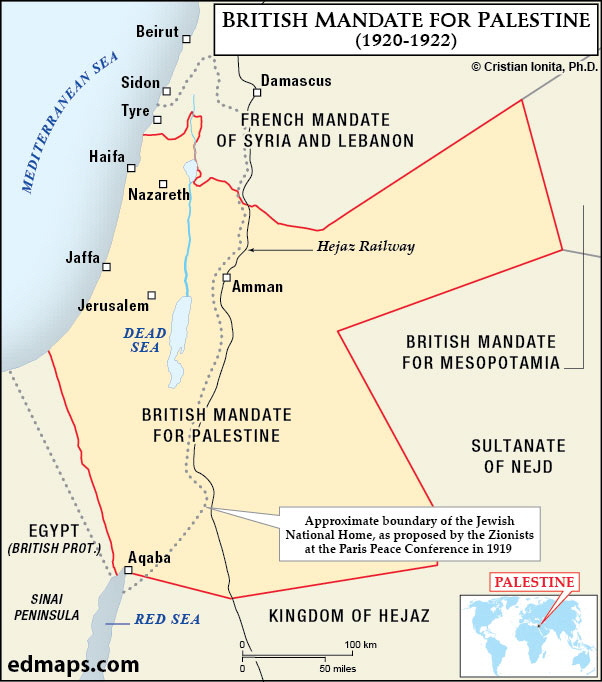

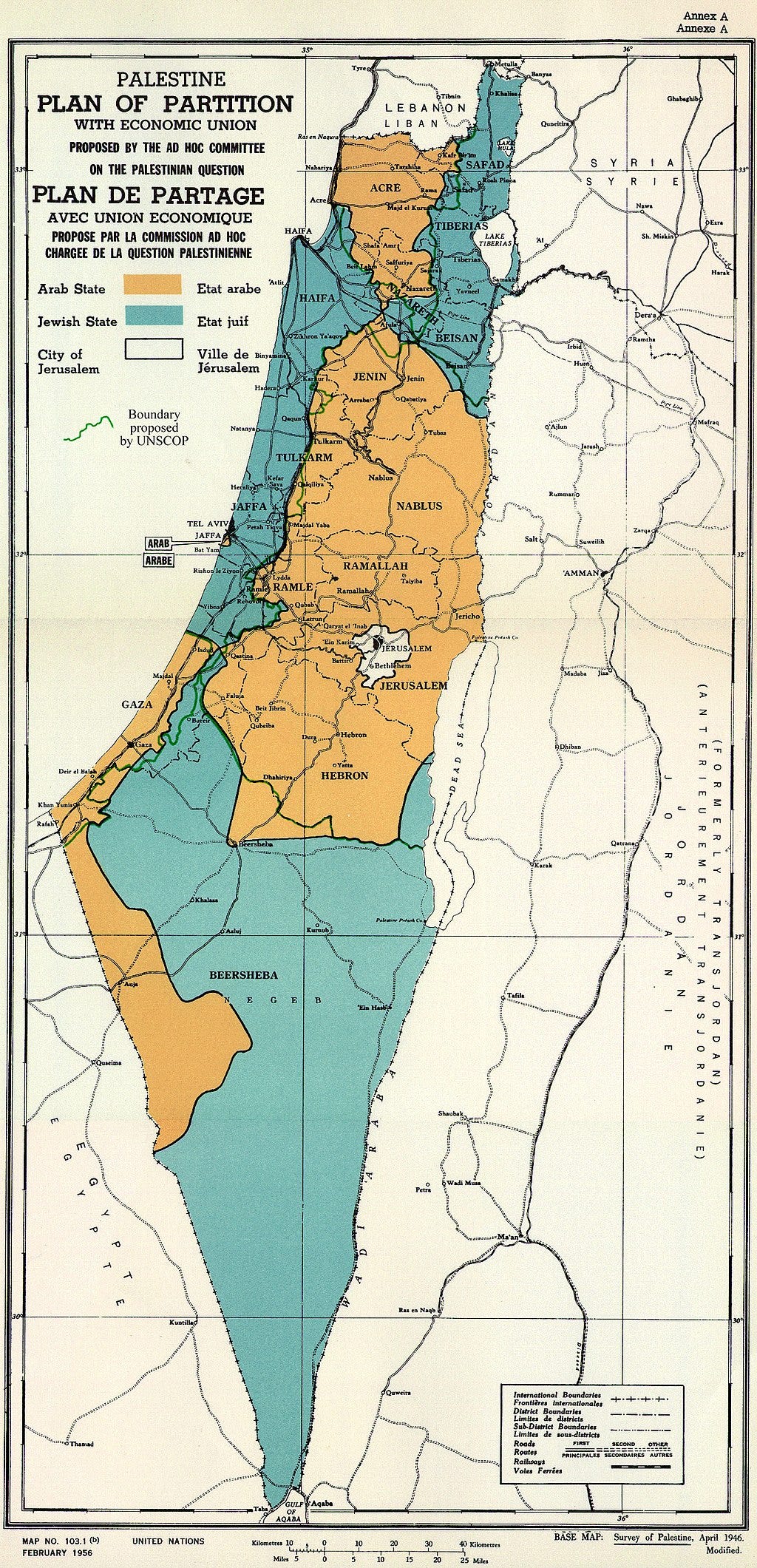

Indeed, the lines on the map often cut right through the land. The border between the Jerusalem and Beirut districts of the Ottoman Empire split the region into multiple sanjuks, which were subdivisions of administrative districts called vilayets. By the time the first Zionists arrived, the land had been split into two vilayets, and incorporated territories not traditionally associated with Palestine.

The last time a sovereign political unit existed in the region, prior to the creation of the state of Israel, was in the 6th century BCE. The name of that state was the Kingdom of Judah.

With this information in hand, we can continue to modify Cooper’s analogy of the Jews who returned to the occupied house. The house is not owned by the Palestinian Arab inhabitants that the Jews find upon their return; it is owned by the Ottoman Empire. Prior to that, it was owned by the Mamluk Empire. And so on, and so on, until we get to the owners who most recently lived inside the house: the Jews. By 1920, the ownership changes hands again, this time to the British Empire. At no point in history do the Arab Palestinians own the house.

At some point in this whole conversation, it becomes natural to wonder: who exactly are the Palestinian people? And why do so many of them have names like al-Masri (literally, “the clan from Egypt”), al-Baghdadi (“the clan from Baghdad”), and al-Farisi (“the clan from Persia”)? Most importantly, why is there no record of anyone with the name “Al-Filistini” (“the clan from Palestine”) prior to the formation of Israel in 1948? Shouldn't we expect to find lots of people in Palestine with the name al-Filistini? Where are they?

I won’t keep you in suspense. The modern-day Palestinian people are the descendants of Muslims and Christians who conquered and subsequently flocked to the region, though some are descendants of Jews who succumbed to the pressure of conversion. None of them possess a national identity continuous with the ancient Philistines. They celebrate no holidays, observe no traditions, and maintain no cultural continuity indicative of any solidarity with that ancient sovereign entity. This raises the question of why they call themselves “Palestinians,” and the answer cuts to the heart of the irony I’ve been alluding to.

They only call themselves Palestinians because this was the name given to the region by the last foreign power to conquer the land. When the British Empire established the colonial entity known as the Mandate of Palestine in 1920, they did so with the understanding that this would be a temporary arrangement. As part of the Mandate system, they would colonize the labor and resources of different regions under the pretext that they were helping the locals establish state institutions, after which they would depart and leave the newly formed states to their own devices.

In the case of Palestine, colonization proceeded mainly through the development of a pipeline running from Mosul to Haifa. It also proceeded, rather substantially, through the procurement of money from Jews who were desperate to return to their homeland. If a Jew wanted to set up a farm on a plot of untouched land, they would not be able to do so for free; they had to pay the colonial power in the region, which extracted this wealth from them to enrich the British Empire.

The local Arabs, however, did not take kindly to the resulting influx of European Jews. By 1948, a nascent Palestinian national identity was forming.

But it was no match for the Jewish national identity, which had withstood two millennia of persecution under exile. This is why, by the time the British left in 1948, the Jews had developed state institutions and cohesive military apparatuses, while the local Arabs had not. The former could unite as a cohesive political unit despite barriers in both language and proximate diasporic history, while the latter could not even agree whether they wanted to be absorbed into Syria, Jordan, or become an independent political unit, despite having a common language and history. The only thing they agreed upon was that the Jews must not have sovereignty anywhere in the land.

Following their defeat in the 1948 war, their resentment and trauma crystallized into what we today recognize as the Palestinian national identity. The story that defines this identity is one which casts Israel as a colonial project of an imperial power, and the Palestinians as a colonized people.

And therein lies the central irony of Palestinian historiography. The name that they chose for themselves–Palestinians–is the name given to the region by the Roman empire to humiliate the Jews. It is the name that condemned the Jews to two thousand years of exile and persecution under Christian and Muslim rule. It is the name given to the region once more by the British colonial power that extorted the wealth of Jews desperate to return home, and which, as we shall see, closed the gates of the homeland just when the Jews needed it most.

This name, Palestine, carries two thousand years of imperial and colonial aggression against the Jewish people. And this is the identity embraced by the side of the conflict presuming to be on the side of anti-imperialism and anti-colonialism. The gods of heavy-handed irony wept.

Assumption #4: The Understandable Resistance of the Colonized

Palestinian historiography insists that the lack of a national identity among the Arabs of the region does not preclude the possibility that they were nevertheless the victims of colonization. After all, Native Americans tribes never had a state of their own, yet who could claim that the European colonists had not colonized them? It’s literally in the name: colonists.

Let’s put to one side the fact that, unlike with Jews and the Holy Land, the European colonists did not have national identities which had formed in the New World, and maintained neither material nor ideological connections to the land in their absence. There is a crucial point that consistently gets overlooked in attempts at characterizing Zionism as a colonial project, and that is the role of exploitation.

“Colonialism” as Euphemism

The dictionary definition of colonialism is “the policy or practice of acquiring full or partial control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically.” I emphasize the conjunctive article, “and,” to highlight the fact that ALL of these criteria need to be satisfied for something to qualify as colonialism.

The “exploiting it economically” part is significant. It represents the entire purpose of a colonial enterprise: to siphon away resources from a colonial outpost to the colonizing motherland. That is the nature of the relationship between colonizer and colonized, and that nature is conspicuously absent from the history of Zionism. The Jews did not siphon away Palestine’s (non-existent) resources to a distant motherland; they were in the motherland, and they invested everything into developing it.

Britain builds a pipeline from Mosul to Haifa to control the region’s oil and enrich the motherland? That’s textbook colonialism. France takes over Morocco and uproots its male population to serve as cannon fodder for the glory of the motherland in the first world war? Again, textbook.

But what are the Jews doing? Throughout the podcast, Cooper uses phrases like “the Zionists were freaking everyone out, kicking down doors and making a big mess,” or, “the Zionists were colonizing the region.” But what was the actual reality on the ground? What happens when we speak clearly in place of these meaningless euphemisms? Truly, I have no idea what “doors” the Zionists kept kicking down, but I’m sure the carpenters in the region are happy with all the business the Jews must be bringing them, what with all these broken doors everywhere.

As it turns out, when we cut the BS and stop using euphemisms, the complaint comes down to the fact that the Jews were moving in and buying private property from Arabs, no longer abiding by the jizya and dhimmitude that the Arabs had grown so accustomed to over the centuries. The Jews were not exploiting the labor or resources of the locals; they were moving in and buying private property, exercising the same property rights that everyone else in the region enjoyed.

And the European Jews that were moving in had, unlike their cousins who’d remained in the Middle East over the centuries, developed an appetite for the Enlightenment. They brought with them such radical notions as equality under the law and freedom of religion–things which had formerly unheard of in the Middle East. These were not the servile, dhimmified Jews that the local Arabs had come to know and expect subordination from. These Jews were free, and the British colonizers who took over the region in 1920 shared these sentiments.

If “colonization” means “de facto overthrowing Islamic traditions of dhimmitude and jizya, and replacing them with western norms of equality under the law,” then sure, colonization proceeded in earnest. By this logic, the American South was “colonized” by the Yankees when they came in and forced a change in the labor laws. Certainly, that’s how the KKK saw it when they subsequently went around, butchering uppity blacks who were exercising their newfound rights; and that’s how the local Arabs saw it when they also went around, killing westernized Jews who had the temerity not to bow to their Muslim masters when they passed them in the streets.

When you say it clearly, without euphemism, the historiography of the Palestinian side gets its door kicked down.

But Cooper is unlikely to be satisfied with this rejoinder. He repeatedly emphasizes that religion is not implicated on the Arab side of the conflict’s origins, and that the fundamental cause of consternation was mass migration from Europe. The problem, Cooper is likely to argue, isn’t that the migrants were Jews; it’s that they were seen as European. We can infer from this that, had mass migration occurred from regions with which the Palestinian Arabs personally identified—say, Arabs migrating from other parts of the Arab World, like modern-day Iraq or Syria—then there wouldn’t have been a problem.

It just so happens that I agree with this last claim. Had Arabs flocked into Mandatory Palestine with the intention of creating their own state from other parts of the Arab-speaking world, then I am certain that there would not have been a century-long conflict between the Old Arabs and the New Arabs. How could there be conflict with migrating Arabs from Iraq, when Palestine was already replete with people whose names literally mean “clan from Baghdad?” How could there be conflict with migrating Arabs from Syria, when Palestine was already replete with people who wanted the region to be absorbed into Syria?

On the surface, this thought experiment might appear to support the claim that the problem was the perception of colonization, not religiously motivated bigotry against Jews. And yet. Consider the following:

Suppose that, instead of Arabs from other parts of the Middle East, it had been Jews from other parts of the Arabian peninsula. Jews from Yemen, Jews from Iraq, Jews from Afghanistan and Libya, all pouring into Palestine, rather than European Jews. All united in their Zionist dream to reestablish their national homeland. What then? Would Cooper expect us to believe that the Palestinians would have been alright with this? That they would have been fine with Jews from other parts of the Arab-speaking world establishing national sovereignty in lands formerly conquered by Muslims?

There is an unambiguously correct answer to this question. It’s the answer that screams out to us when we study the histories of other ethnic minorities within lands conquered by Muslims, from Druze in Syria to Maronites in Lebanon, from Bahai in Iran to Kurds in Iraq. It’s the answer that screams out to us when we examine the Palestinian attitude towards Israel after the surrounding Muslim countries applied intimidation, political violence, and in several cases, bloody pogroms, to ethnically cleanse themselves of 900,000 Jews, most of whom fled to Israel; to this day, Israel enjoys a majority population of Jews descended from the Arabic (as opposed to European) diaspora, but this fact has done nothing to assuage Palestinian hatred.

The answer to our thought experiment continues screaming out to us when we read their slogans (“The Jews are our dogs!”), their picket signs (“Water to water, Palestine is Arab!”), and even their creative works. Here is a poem authored by Sheikh Sulayman al-Taji (al-Faruqi) in a November 1913 issue of the Jaffa Arab daily Filastin, summarizing the widespread attitude of Jewish land purchases from the local Arabs:

Jews, sons of clinking gold, stop your deceit; We shall not be cheated into bartering away our country! . . . The Jews, the weakest of all peoples and the least of them, Are haggling us for our land; how can we slumber on?

Keep in mind, this was November 1913. British colonization of the region would not take place for another seven years, and Israeli independence would not be declared for another thirty-five. They are not confused about who the migrants are. They are not complaining about European aliens. They are complaining about Jews.

The results of our thought experiment suggest that the conflict is not simply about European colonization but about Jewish sovereignty itself, which would have been resisted regardless of the Jews’ geographic origin. Islamic traditions of dominance over non-Muslim minorities played a significant role in shaping the Arab response to Jewish sovereignty, and the efforts of Palestinian historiographers (and, by extension, Cooper) to downplay this fact is revealing.

What’s the Evidence for Colonialism?

The accusation of Jewish colonization over the region is restricted to two lines of evidence: written records by important Zionist figures and institutions, and the presence of a European colonial power that facilitated Zionist migration. Neither of these survive scrutiny.

The founder of Zionism, Theodor Herzl, is cited by Palestinian historiography as having introduced colonialism into the Zionist project from the outset. Evidence supporting this claim is derived principally from passages of the movement’s foundational text, The Jewish State, as well as unsent personal correspondences to colonial figures like Cecil Rhodes.

Derivatives of the word “colony” appear eight times in The Jewish State, and in no instance does it entail the forceful removal or exploitation of the land’s current inhabitants. A characteristic passage reads:

Should the Powers declare themselves willing to admit our sovereignty over a neutral piece of land, then the Society will enter into negotiations for the possession of this land. Here two territories come under consideration, Palestine and Argentine. In both countries important experiments in colonization have been made, though on the mistaken principle of a gradual infiltration of Jews. An infiltration is bound to end badly. It continues till the inevitable moment when the native population feels itself threatened, and forces the Government to stop a further influx of Jews. Immigration is consequently futile unless we have the sovereign right to continue such immigration.

The Society of Jews will treat with the present masters of the land, putting itself under the protectorate of the European Powers, if they prove friendly to the plan. We could offer the present possessors of the land enormous advantages, assume part of the public debt, build new roads for traffic, which our presence in the country would render necessary, and do many other things. The creation of our State would be beneficial to adjacent countries, because the cultivation of a strip of land increases the value of its surrounding districts in innumerable ways.

In this context, Herzl’s use of the term “colonization” refers not to the formal practice of colonialism, in which invaders subjugate and exploit a land and its people, but to the innocent practice of establishing a community. The Oxford English Dictionary records the following definitions of the word “colony”:

a country or area under the full or partial political control of another country, typically a distant one, and occupied by settlers from that country.

a group of people of one nationality or ethnic group living in a foreign city or country.

In the parlance of the late 1800s, when Herzl was writing his document, one could sensibly refer to today’s community of ethnic Iranians living in Los Angeles as “the Persian colony” without implying anything sinister about their intentions. What Palestinian historiographers have effectively done with such passages is to equivocate between the innocent sense of the term that Herzl was using with the sinister meaning associated with characters like Cecil Rhodes.

Speaking of which, Herzl’s unsent correspondences with Rhodes does not provide evidence of colonization in the latter sense of the term. The invocation of Rhodes in these discussions seems to function as little more than an attempt at establishing guilt by association. Nowhere in Herzl’s drafted correspondences is there any talk of establishing an operation aimed at extracting wealth from the land, as Rhodes had done with the diamond fields of South Africa. Upon closer inspection, it becomes evident that the use of the term “colony” and its derivatives in Herzl’s written works, correspondences with Rhodes, and organizations like the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association, does not provide evidence of plans to exploit or subjugate the Arabs of Palestine.

Neither does the fact that Zionists tried to work with the Mandate system from 1920 onwards to facilitate their project. The Balfour Declaration of 1917, in which the British Empire declared its intention to establish “a national homeland for the Jewish people,” does not reflect any desire on the part of Jews to economically exploit Palestine to enrich some distant motherland.

The fact that Great Britain intended this for itself is immaterial to the accusation being directed at Israel. In any complex act of statecraft, many people with different motivations will be involved, and people out of power—like persecuted Jews fleeing Europe—will be forced to do business with whoever happens to be in power.

From 1882 to 1920, the Zionists did business with the Ottoman Empire. It doesn’t follow from this that Zionism was therefore an imperial enterprise. Similarly, the presence of Brits in Palestine who wanted Jews to leave Europe out of feelings of antisemitism, or who wanted Jews to establish their state out of apocalyptic theological convictions, does not imply that the Zionist project was predicated upon the hatred of Jews or the desire for Jesus to return. And likewise, the presence of Brits who imposed a colonial enterprise over the land does not imply that the people who were forced to do business with them–including both Jews and Arabs–were themselves engaging in colonialism.

The Role of Eviction and Radicalization

None of this should be taken to imply that the Jews acted like saints. As Herzl himself wrote in his diary:

We must expropriate gently the private property on the estates assigned to us. We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it employment in our own country The property owners will come over to our side. Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly.

The way it went down was like this. Zionist organizations would coordinate the financial, logistical, and political resources necessary to move Jews from Europe to Palestine. Funding was procured through philanthropic and lobbying efforts with various governmental agencies, and upon arrival, newly emigrated Jews would be provided training and housing to help build the country.

Land for businesses and farms was purchased either directly from the landowners, or indirectly from the empire in charge if there were no private owners. Exact figures are difficult to come by, but according to the Peel Commission of 1937,

The shortage of land is due less to purchase by Jews than to the increase in the Arab population. The Arab claims that the Jews have obtained too large a proportion of good land cannot be maintained. Much of the land now carrying orange groves was sand dunes or swamps and uncultivated when it was bought… The shortage of land is, we consider, due less to the amount of land acquired by Jews than to the increase in the Arab population.

Of the land that had been peopled, the majority of tenants were subsequently evicted. There were exactly zero cases of land being forcibly seized from the original Arab landlords.

Most of this business took place from 1901 to 1925 with the Sursock Purchases, which according to a 1946 memorandum published by the Arab Higher Committee accounted for around 60% of the subset of land purchases in which prior tenants were evicted. According to the Shaw Commission, this purchase reflected an eviction of around 1800 families.

The total number of Arabs evicted from Zionist land purchases can be estimated after granting generous assumptions that inflate the true figure. Rounding the number of families evicted in the Sursock Purchases up to 2000, and estimating an average of ten family members per household, we arrive at a figure of twenty-thousand evictees. Double that to account for the remaining 40% not accounted for by this specific set of purchases, and you get a total figure of no more than forty-thousand Arab Palestinians who were evicted due to Zionist land purchases. This accounts for 3% of the Arab population in Palestine in 1946.

I don’t deny unpleasantness of forced eviction, especially in cases where evictees had been tied to the land for multiple generations. But I do deny that, accumulated over 3% of the population and over the course of sixty years, this constitutes such a serious breach of the social contract as to warrant the immense violence that the Palestinian Arabs unleashed upon the Jews from 1920 onwards.

I will have much more to say on this subject in the next section, but beginning in 1920, the Arabs of Palestine enacted escalating acts of mass rape and murder. This culminated in a pogrom in the city of Hebron, which ultimately resulted in the ethnic cleansing of its Jewish population—a population consisting principally of families that had resided there for eight centuries.

These escalating acts of violence, which continued into the thirties through the Arab Revolts, had the effect of increasingly radicalizing the Jewish population. Contrary to Cooper’s suggestion that it had been the Zionist firebrand, Vladimir Jabotinsky, who’d radicalized the Jews, every indication is that it was the violence of the Arabs themselves that led to the increasing militancy of the Zionists.

The most moderate of the self-defense organizations formed by Zionists in response to the escalating violence of Arab Palestinians, the Haganah, was formed in 1920 after the Nebi Musa riots, of which more will be said later. This force consisted mainly of untrained Jewish farmers who took turns defending their settlements, but became more centralized and professional in response to the ethnic cleansing of Hebron in 1929.

In 1931, a paramilitary organization called the Irgun was created. It was rooted in the more radical ideology expressed by Jabotinsky, which vascillated between endorsements for colonialism (by which I mean the actual kind), and appeals to more liberal solutions to Zionist problems; the attitude he endorsed varied largely as a function of his mood at the time of writing.

It will come as little surprise that Palestinian historiographers love to quote the things that Jabotinsky wrote in his more fiery moods as evidence that Zionism was an inherently aggressive enterprise. Cooper himself quotes Jabotinsky extensively in his podcast in support of this thesis. But it is important to remember that Jabotinsky’s ideology was accepted by only about 1% of the Zionists when he first came onto the scene, and never entered the double digits until after the Palestinian Arabs had ethnically cleansed Hebron. Regardless, it never enjoyed anything close to majority support from Zionists; the overwhelming majority adhered to more moderate variants of the ideology.

To Cooper’s credit, he does at some point acknowledge that Jabotinsky was much less extreme and much more liberal than his opponents give him credit for, but we’re never presented any evidence to support this. We are only ever treated quotes about his expansionist and colonial dreams, and never quotes like the following:

I never said that [Zionists ought to expel Arabs from Palestine], or anything that could be interpreted in this sense. My position is, on the contrary, that no one will expel from the Land of Israel its Arab inhabitants, either all or a portion of them—this is, first of all, immoral, and secondly, impossible.

Even “radical” Jabotinsky had maintained repeatedly that Arabs living inside of the Jewish state ought to be granted equal rights under the law. And this remained his position, as well as nearly everyone else’s, throughout the episodes of violence and mass murder that repeatedly plagued Jews in Mandatory Palestine. True enough, the Zionists had increasingly developed an appetite for Arab expulsion as the Yishuv (the Jewish community in the Land of Israel) was treated to pogrom after pogrom, but it never became an officially endorsed feature of state policy. There will be much more to say about the mechanics of the Nakba later on in this essay, but suffice it to say that the mass expulsion of Arabs from Palestine was ultimately carried out not as a matter of express Zionist principle, but as an inconsistently applied military directive during a defensive war, and almost exclusively in response to evolving situations on the ground.

Returning to the subject at hand, the true radicals of the Zionist movement emerged in 1940 with the formation of the terrorist organization, Lehi. It was a deeply unpopular group that attempted to form an alliance with Nazi Germany, was roundly condemned by nearly all the Jews in Mandatory Palestine, and never numbered greater than one thousand. More will be said about their role in the conflict in the next section.

For now, let us close with a summary of this fourth and most crucial of assumptions advanced by Palestinian historiography. By casting Zionists and colonizers and the Arabs of Palestine as colonized, Cooper dutifully recites the framework that sanitizes Palestinian violence against the Jews as a form of understandable (if not necessarily justifiable) resistance.

The characterization of Zionism as a colonial enterprise fails to hold up under scrutiny when the actual definitions and historical practices of colonialism are considered. Unlike colonists of the sort alluded to by those who charge Zionism with this term, the Jews did not arrive in Palestine to exploit its resources and send wealth back to a distant motherland. Instead, they invested in developing the land they viewed as their ancestral home. The practices of economic exploitation and forced displacement that are central to actual colonial endeavors are not reflected in the actions of Zionist settlers who purchased land and sought to integrate—albeit contentiously—into the region.

Furthermore, the assertion that Zionism was merely a form of European colonialism overlooks the complex religious and national dynamics at play, revealing a deeper conflict rooted in identity and sovereignty rather than simple colonial ambition. Upon scrutinizing the terms and historical context, it becomes clear that the shoe of colonialism will not fit the foot of Zionism, no matter how much twisting of the original definition or cherry-picking of nonrepresentative quotes one engages in.

Assumption #5: The Jewish Question

“What did the Jews do to earn the violent treatment that they suffer, and have long suffered, at the hands of the Palestinians?”

This is the principal question that Palestinian historiography builds towards in its quest to legitimize the long-doomed project of undoing Israel’s existence. In the Arab-speaking context, it has a simple answer.

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was translated into Arabic in 1920, which incidentally was the year that Arab violence against the Jews escalated in the aforementioned Nebi Musa riots. Its influence on the closest thing the Palestinians had at the time to a leader of a national movement, Haj Amin al-Husseini, was profound. He was the leader of the notable al-Husseini clan, the head of the Arab Higher Committee, and the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem. Today, he is largely remembered for his activities during the years of World War 2: living in Berlin, befriending Hitler and Himmler, recruiting Bosnian Muslims to the SS to enthusiastically enact the Final Solution, and transmitting Hitlerian bile over the radio to Arabs back home. He also supported the 1941 Axis-backed coup in Iraq, instigating a pogrom in the process against the ancient Jewish community that resided there. 180 Jews were murdered in what came to be known as the Farhud (“violent dispossession.”)

This is an abridged history of how Islamic antisemitism, previously restricted to a theological character of the sort already discussed, took on the worst aspects of its European counterparts. The result today is a shocking degree of dehumanization and paranoia about Jews in the Arab-speaking world, normalized to the point where antisemitic tropes are widely internalized and casually repeated by enormous swathes of Arab-speaking populations.

This makes for ineffective propaganda when targeting Western populations, which are far less receptive to such rhetoric. It would not be until the 1960s when, with the aid of Soviet institutions wielding ready-made templates for postcolonial historical revisionism, Palestinian leaders and intellectuals would present a historiography more palatable to the West. That historiography, which Cooper has enthusiastically recited on his podcast, has been the subject of this essay.

And it is on the subject of the Jewish Question that Cooper’s distortions of the historical record, inherited from the Palestinian historiography that he uncritically parrots, are so vast in their number and severity as to warrant a harsher tone in the course of correcting them. The answer to the Jewish Question in the English-speaking world is: “The Jews punished Palestine for the sins of Europe.” And this is the answer that Cooper embraces.

The Roaring 20s

The years leading up to 1920, from 1882 onwards, had not been as peaceful as Palestinian historiography often suggests. The violence began as early as the mid-1880s, and broke out intermittently thereafter. In every instance, the instigators were the Arabs. By April 1914, the British consul in Jerusalem was reporting that the assaults upon Jews in the outlying districts were becoming increasingly frequent. The reason Palestinian historiographers remain silent on these early skirmishes is because their narrative claims that the conflict began in 1917 with the issuance of the Balfour Declaration. Starting the clock any earlier runs the risk of suggesting that the conflict began prior to the involvement of a colonial power, and such an admission threatens Assumption #4. What is all sides do agree on, however, is that the violence radically escalated from 1920 onwards.

By 1920, according to Cooper, the Jews have done much to invite a violent response.“Completely unjustifiable of course,” he maintains with a clear of his throat, before proceeding to explain why the rapes and murders that followed are “nevertheless understandable.” After euphemistically referring to Jewish land purchases and evictions with that omnipresent phrase, “they were kicking the door down all over the place,” he finally explains what happened.

An annual festival marking the traditional Islamic pilgrimage to the shrine of Nabi Musa, purportedly the tomb of Moses, took place in the spring of 1920. As the procession of devout Muslims made its way through the Old City of Jerusalem, the atmosphere became charged with conflict.

The previous month, an Arab militia had attacked and destroyed the Jewish settlement of Tel Hai, which they’d initially expected to be harboring enemy troops in the ongoing Franco-Syrian war. Following a misunderstanding, a firefight broke out, and eight Jews and five Arabs were killed. When it was done, the Arabs burned Tel Hai to the ground. It wasn’t the first Jewish settlement to have been attacked and destroyed by local Arabs since the Zionists started arriving, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last.

Now, a month later, tensions soared between the local Arabs and Jews. Zionist authorities had noted the lack of armed British police and soldiers, raising concerns about their ability to maintain order in the upcoming festival. Requests for additional law enforcement were denied. Consequently, a group of volunteers, consisting largely of local sports clubs and a handful of veterans, came together to train in calisthenics, practice hand-to-hand combat with sticks, and marched in formations to coordinate defense in case the need arose.

It was wholly inadequate. Tens of thousands of Muslims flooded into the Old City on the morning of April the 4th. By 10:00 in the morning, there were already attacks on Jews in the alleyways of the city. The aforementioned Grand Mufti–the one who ended up befriending Hitler–delivered a fiery speech to the crowd, which was already agitated by the defiant posture of the European Jews who were not conducting themselves in the servile manner befitting a dhimmi. His uncle, the mayor of Jerusalem, stoked the flames of Jew-hatred with a speech of his own.

It was at this time that the crowd began chanting, "Palestine is our land, and the Jews are our dogs!" When Arab police joined in on the applause, the riot broke out. A pogrom followed.

Jewish shops, homes, and individuals–regardless of whether they had been around for centuries, or days–were targeted by the mob. The looting, burglary, arson, and murder continued for five days. The diary of a Palestinian teacher, who had witnessed the events firsthand, recounted how the mob had shouted, “Muhammad’s religion was born with the sword!” Several Jewish women were raped in the streets of Jerusalem.

By the time the British finally restored order, a handful of people had been killed, but over two hundred Jews had been injured. In contrast, only a couple dozen Arabs experienced injuries.

Perversely, Cooper suggests that the fault of the Nebi Musa riots ultimately rests with vaguely worded “Zionist provocation.” He alludes to the marches undertaken by the volunteer defense force, Zionist slogans declaring their intention to establish a national homeland, and the ongoing land purchases (“kicking down the door,” in his parlance) that were evicting an underwhelming minority of the local Arabs. These, he insists, were the root causes of the violence. In so doing, Cooper maintains that time-honored tradition of Palestinian historiography in which Arab responsibility is downplayed through vague gestures towards Jewish “misbehavior.”

Please try to understand what Cooper is attempting to convince us of. Religious Muslims, many of whom were pilgrims to the region with little knowledge of the conflict, who listened to inflammatory speeches given by their spiritual leader in the Old City, who chanted religiously-motivated expressions of Jew-hatred and violence, and who targeted Jews irrespective of their affiliation with the Zionist movement—these people, Cooper insists, were not principally motivated by theological considerations. They were just resisting colonization in the only confused, angry, and misguided way they knew how.